53 Fremont Place

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

WILSHIRE BOULEVARD ADAMS BOULEVARD BERKELEY SQUAREWINDSOR SQUARE ST. JAMES PARK WESTMORELAND PLACE

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO FREMONT PLACE, CLICK HERE

The megalomania that drives movie stars and oil princes to build outsized houses in Los Angeles today is actually part of a long tradition; just as often it has been a childless businessman and his wife who have felt the necessity to build vastly more house than is practical as James and Maud Shultz did when they commissioned 53 Fremont Place in 1919. The results of such lavishness in today's efforts seem to pale in comparison to those, such as 53, built before the Depression; with architects given carte blanche once better able to corral their own fantasies within tradition—and actually educated to respect the vernacular—the results were better composed than the farcical resorts-as-private-houses despoiling Beverly Hills and Bel-Air, among other suburbs, today. Once upon a time, architects such as Henry Harwood Hewitt understood that aside from a fat paycheck and a roof over a client's head, charm was the whole point.

|

| The journal California Outlook covered the Progressive movement during the 1910s. Its issues were full of advertisements of, and tributes to, businesses and professionals presumably supportive of the party line. An ad with a view of James Shultz's lumber yard south of downtown appeared in the May 25, 1912 number. Shultz sold the business soon after he used the yard's finest inventory of build 53 Fremont Place in 1918. |

The James and Maud Shultz were among those prosperous Angelenos who wisely invested in residential real estate as their fortunes rose. Their marriage appears to have been one of immigrant drive (his) combined with native California spunk (hers); born on May 17, 1870, in territory long wrangled over by Germany and Denmark, Shultz left Europe at 16. After some time in Clinton, Iowa—even he would arrive in Los Angeles with Midwestern credentials—he made his way to San Francisco, where he was naturalized in July 1892. Within six years, he had moved south to Redondo Beach to manage the Redondo Lumber Company. Moving to the company's offices in Los Angeles by 1898, he married Maud Hudson Richardson, born in Bakersfield, in September of that year, an event covered in the Times and the Herald—James Shultz was a young man who was being noticed and Maud was the stepdaughter of an established downtown paint dealer. With no children arriving, the Shultzes' resources of money and time were turned to real estate speculation. After a few years in small houses in the largely extant but overlooked swath of Victorian cottages straddling Main Street south of Adams, the couple regrouped and moved to the fashionable Fremont Hotel on Bunker Hill—an early bit of real estate honoring explorer and politician John C. Frémont and a precursor to the Shultzes' future home west of town. Among their real estate investments was a lavish house at 248 Occidental Boulevard described by the Herald as "one of the handsomest in the city." Its downstairs rooms were paneled in curly redwood—James had access to the best woods, of course—there was a conservatory and a roof garden, and, in another precursor of 53 Fremont Place, a Spanish design motif including cathedral windows, a red-tile roof, and a tower—built, it would seem, for the ages.

|

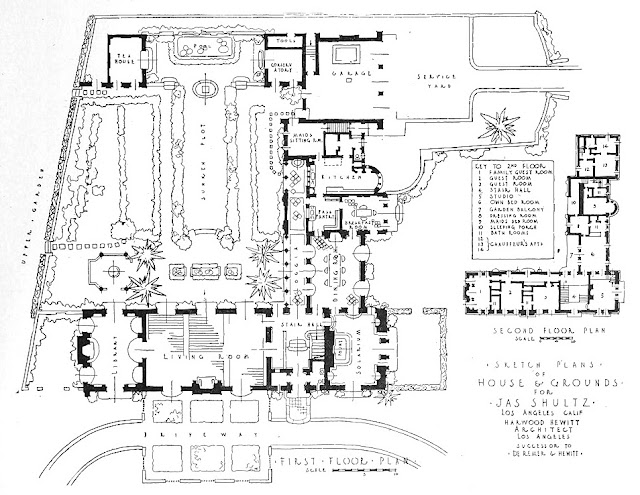

Architect Harwood Hewitt's full composition as viewed northwesterly from the easterly drive of Fremont Place and West Eighth Street; interesting is that as elaborate as the house was, there was no porte-cochère, these architectural elements having become irrelevant to some homebuilders in sunny California. Below is a schematic by Hewitt that appeared in The Building Review in May 1923, according to which the tall windows at left belong to a room described as a "studio." |

While some people do indeed build for the long term, some build just for the pleasure of the project—the childless Shultzes, with little to distract themselves in a house of many rooms, were of the latter sort. They sold 248 Occidental Boulevard without moving in and remained at the Fremont Hotel. More projects were in the pipeline, however. Lots in the rapidly emerging western Wilshire district were purchased as investments, for one of which, at 625 South Harvard Boulevard in the Normandy Hill tract, the Shultzes commissioned another house in a Spanish vein. They would move into this one in 1910 and stay for all of six years—which is not to say that they settled down. Their real estate investing continued; 625 South Harvard was sold (it later became an annex of the Wilshire Boulevard Temple) and the Shultzes moved into 1806 West Sixth Street, where during 1917 Harwood Hewitt came to lay his renderings for the latest and greatest of the couple's domestic endeavors on the dining room table for inspection—Shultz, an acquaintance of Fremont Place developer David Barry, had just bought Lot 35 and the east 30 feet of Lot 37 in the subdivision. Hewitt's plans included a garage, bird house, tea house, plastered fences, and a well house. By this time, James Shultz had risen in the lumber world; having been associated during the aughts with the prominent E. K. Wood Lumber Company, he had incorporated his own James Shultz Lumber Company in May 1910. Again, only the best lumber would finds its way into 53 Fremont Place, as the corner was addressed when the house was completed. Here would be another place "reminiscent of Spain and days of romance in the early history of California.... Admirably fitted for a setting of rolling land near mountains in a country of bright sunshine and long weeks without rain," as The American Architect and the Architectural Review put it in 1923. There was, of course, a red-tile roof (by the famous L.A. Pressed Brick Company, toppers of many area houses), as well as grillwork, cathedral windows, and rounded details to soften the bulk.

|

| A view of the southeast corner of 53 Fremont Place before a looming condominium replaced northerly blue skies 60 years later; it and a detail of the house's entrance gate and stair tower appeared in The American Architect and the Architectural Review in 1923. |

In the end, it seems that all the romance conjured up by their architectural pursuits—and their extensive travels—couldn't hold together what appears to be a deteriorating marriage. After more than 25 years and less than seven or so at 53 Fremont Place, the Shultzes parted company. Their house was being advertised for sale in the Times in January and February of 1927 and they divorced that year, James settling $219,900 on his ex. It seems that after years in the lumber business, which he left soon after moving to Fremont Place, and sitting on corporate boards with the likes of Marco Hellman, Henderson Hayward, Louis M. Cole, and W. D. Woolwine, he wanted to move on to ranching in the San Joaquin Valley and tuna-fishing off Catalina; for her part, Maud appears to have found a new interest, one other than the planning and building of houses. A Mr. William R. Inghram had entered the picture, if not for long. Filing in Reno in September 1929 to obtain a second divorce (records are unclear as to whether the action went through), Maud was soon living in a small house—with a red-tiled roof—on Harper Avenue; all the romance was gone. According to the Times, after she died on March 11, 1934, William Inghram, who had been left nothing, filed a lawsuit to contest her $90,000 estate (where $129,900 had gone in seven years was not reported) and charged that Maud had been dominated by his predecessor. The case was settled on unknown terms. James Shultz went on ranching and fishing and traveling and died in Fresno on March 23, 1957.

|

| An aerial view of the east façade of the James Shultz house reveals a largely original building that could quite possibly retain its original roof installed in 1918. Fremont Place was opened in 1911; it was laid out on largely treeless plain as was much of the larger district, which included Windsor Square and yet-to-open Hancock Park, collectively referred to broadly at the time as the "West End" of Los Angeles. |

Upon the untimely death of the architect in January 1926, Harwood Hewitt's 53 Fremont Place was cited by his professional peers as one of the finest buildings in Los Angeles. Yet for all of its appeal to the imagination—not to mention its space—the house was destined, for at least another couple of decades after the departure of the Shultzes, to be inhabited for the most part only by couples with no children. It is unclear as to whether the Shultzes' successor bought the house in 1927, or rented it; his stay was short and his use of 53 may have been as more of a pied-à-terre than a permanent residence. Frederick William Matthiessen Jr. was from a very rich and distinguished family with, like James Shultz, Danish roots. Rather than self-made, Matthiessen was well-funded and well-connected to the American establishment from the get-go. His father, the original immigrant, was an originator of the zinc industry in America with the good timing to be able to supply matériel during the Civil War. F. W. Matthiessen Sr. also bought and rejuvenated the Western Clock Company, which became Westclox, producers of Big and Baby Bens. Junior, born in Illinois on April 27, 1871—the Midwest, it seems, being where all proper Fremont Placers must incubate—grew up to take over the clock works and to produce four children by the first of his three spouses. Not long after the 1902 birth of his youngest child, who became the brilliant Harvard professor Francis Otto Matthiessen, he divorced his first wife, Lucy; he divorced his 20-year-younger second wife, Elsie, after seven years in 1924, soon after buying 532 Lorraine Boulevard over in Windsor Square. Matthiessen then promptly and secretly married for a third time; Kitty Moran was 27 years younger. The newest Mr. and Mrs. Matthiessen tried living in Santa Barbara for a time; perhaps there was disinterest among the matrons of that city in the new Mrs. Matthiessen, or hers in them, or it was the June 1925 earthquake, or it was the various antics of son-of-a-different-stripe F. W. Matthiessen III (the Santa Ynez Valley rancher was arrested that November, accused of stealing a friend's Liberty Bond and silverware), but Junior and his new wife were before long looking to resettle in Los Angeles. Matthiessen opened a downtown office and acquired the Shultz house by one sort of transaction or the other. Whether bought or rented, the Matthiessens' stay in Fremont Place was brief. A somewhat less sophisticated crowd was 53's next act, one that, once again, was brief.

Movie folk were not unknown to Fremont Placers; among others, no less than Mary Pickford and Mary Miles Minter had both occupied 56 a decade before and Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures had moved into 135 by 1927 and stayed for many years. The new owner of 53 was actually the widow of a showman. Joseph Lafayette Rhinock was a colorful Kentuckian who was mayor of Covington for seven years and then elected to Congress for three terms. He was in the oil-refining business and had large interests in horse tracks; his showbiz endeavors included the vice presidencies of the Shubert Theatrical Company and the Loew's theater circuit. He married Emma McKain in 1883 and had five children, the oldest of whom, Robert, died in 1901; the marital comings and goings of the rest could fill a book. Alma, the youngest, eloped in 1911 and was soon divorced and later remarried. Hazel Myrtle also married, divorced, and married again. Frank's wife Lillian divorced him, remarried him, and divorced him again. Laura married, had a baby 10 months later, then divorced the father for infidelity; facilitating a search for another husband, Joe and Emma would helpfully take the baby, named June, off her mother's hands by adopting her as their sixth child in 1920. In January 1926, Variety reported that Laura had recently attended a movie screening of The Merry Widow with her father in New York, immediately gotten on the California Limited, and was within weeks married to one of the film's stars, Roy D'Arcy. They divorced and remarried and divorced again as messily as had Frank and Lillian. Amid the commotion, Joseph Rhinock died in September 1926. Once his estate shook out, Emma was left with a couple of million or so. She set out for Los Angeles and took an apartment at the Los Altos from which to hunt for a house; by the end of 1929, she and June were ensconced just up Wilshire at 53 Fremont Place with a cook and a houseboy. Before long, after divorcing D'Arcy for the second time, Laura moved in with her mother and sister-née-daughter. Then she married for a fourth time and brought eight-year-younger George Wright, described as a film director, home to 53. The bite he suffered when he stopped his car to help an injured dog in October 1932 was just the beginning of his troubles; though it was soon to be downsized dramatically, perhaps it was the style of the Rhinocks' life that appealed to him initially as much as had Laura; at any rate, his new wife would prove to be more than he could have bargain for.

|

| Although she inherited a sizable fortune from her husband, movie executive Joseph Rhinock, Emma Rhinock may have overextended herself with the purchase of 53 Fremont Place; the cash demands of her much-married children and her poor timing—she moved in just as Wall Street, as Variety put it, laid its egg in October 1929—made the family's stay short. Advertisements for auctions of her furnishings appeared in Los Angeles papers in February 1933. |

With the Depression reaching its nadir and so many family members (and their attorneys' accounting departments) snapping at her pocketbook, Emma Rhinock very likely found herself dipping deep into capital to support the household at 53 Fremont Place. Soon after George was bitten by the dog, the family moved out. Large display advertisements appeared in the Times in February 1933 announcing a series of auctions of the house's contents. "The magnificence and grandeur of this palace beggar description," the ads read. Whether the house itself was retained by Emma pending its sale is unclear; there was no mention in local papers of foreclosure or of there being a new owner of what was by 1933 one of many white elephants then spread across Los Angeles. The Mediterranean style was already being looked at as a fusty artifact of the '20s, perhaps too much of a reminder of better times. Unlike many big houses, 53 managed to survive, as did, more or less, the Rhinocks. By 1936, Emma, June, and Frank and his new wife Elma (Emma, Alma, Elma...) were living at the Peter Pan apartments on Burnside Avenue—Frank was the manager. Perhaps there was enough of Joe Rhinock's bounty left to buy the building, which, offering a roof over their heads and income to boot, would have been a wise investment. Laura and George do not seem to have moved into the new family compound; as she deteriorated deep into alcoholism and worse, George, in fact, seems to have soon departed the family scene. In December 1934 Laura had been charged with writing checks for which their were insufficient funds in her account; she blamed her confusion on a doctor she claimed had gotten her addicted to narcotics. As the decade progressed, Laura Rhinock Duffy D'Arcy DArcy Wright only became more ill. After having been committed to the California State Hospital at Patton twice for rehabilitation, she was found wandering aimlessly near Echo Park in early June 1939 with wounds she claimed came from an attack by an ax-wielding perp; June, who had already been married and divorced, committed her mother/sister back to Patton, where, sadly, Laura died on June 10.

|

| "It was one of those California Spanish houses everyone was nuts about 10 or 15 years ago." As spoken by Fred MacMurray in the movie Double Indemnity, the line suggested how quickly the style had passed out of fashion once the Depression took hold. Descriptions of the houses built as part of the Mediterranean craze in Southern California during the '20s varied from Spanish to Italian to, by 1979 when this advertisement appeared in the Times on December 1, "San Simeon–Style." Even 50 years later—before a recent re-appreciation—"Spanish" was likely to suggest the outmoded style of house caricatured in Sunset Boulevard, seen here. |

No doubt long forgotten by the preoccupied Rhinocks, the house at 53 Fremont Place did not languish for too long after their departure despite appearing to be the relic of another age to some. Its being oversized (and very possibly suffering from deferred maintenance as well) would to the discerning be mitigated by the charm of Harwood Hewitt's design and the quality of its construction, which have contributed to the house now having lasted nearly a century; one such discerning couple in the mid-'30s were the William Hilton Crofts of Chicago. During the decade, Chicago-born William Croft was consistently one of the highest-paid executives in the country—in 1934, the highest paid—as vice-president of the National Lead Company and president of its Magnus Metal Division. Croft and Mae Tillotson had married in 1904 and raised three children; to the couple, now in their 50s, getting away to California from gray Chicago became a priority once the children were grown, at least for the winter. To their Midwestern-bred eyes, 53 Fremont Place would have seemed like a mirage, and, at its reduced Depression valuation, a mere bagatelle in terms of price. With their children back east, William and Mae Croft would still be at 53 when he died at his brother-in-law's Beverly Hills house in 1949. Their son, William H. Croft Jr.—also in metals—would have an eight-year, high-flying Sutton Place soap opera of a marriage well-covered in national papers; suffice it to say among its strange highlights were dramatic reconciliations and, before the inevitable 1941 divorce, a wife committed to a Wisconsin asylum who then ran off with another inmate to New Orleans, all of which she claimed was made during a trance induced by a white powder at the beginning of the adventure; Beverly Croft was found dead after three days at the St. Moritz in New York in December 1948. Meanwhile, in California, 53 Fremont Place remained an oasis for the senior Crofts, its Spanish visage and morning sun coming through its tall cathedral windows doing the job that Harwood Hewitt intended. The house remains in all its splendor, marred only by the seven-story Wilshire-facing condominium that opened next door in September 1980 as the density of Los Angeles's old Park Mile began in earnest.

|

| As the push for the density of Los Angeles toward that of once-scorned New York increases in the 2010s, high-rise apartment buildings, such as the early example at 4460 Wilshire Boulevard looming over 53 Fremont Place—with a subway soon to run out front—are promoted by developers as the California dream of the single-family house is demonized. Despite the entire subdivision nearly being lost in a commercial redevelopment plan at a low point of the district's residential favor after the turbulent '60s, what was once the "West End" of the city has gained new appeal. |

Illustrations: The American Architect and the Architectural Review; California Outlook; The Building Review; Reddit Floorplans; LAT; GSV